The Physiologist Magazine

Read the Latest Issue

Don’t miss out on the latest topics in science and research.

View the Issue Archive

Catch up on all the issues of The Physiologist Magazine.

Contact Us

For questions, comments or to share your story ideas, email us or call 301.634.7314.

Human Cells, Not Prison Cells

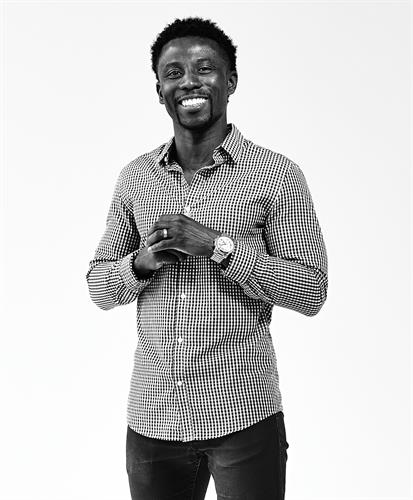

For Stanley Andrisse, PhD, physiology opened the door to a fulfilling life.

By Heather Boerner

It was at night that Stanley Andrisse, PhD, would pore over scientific articles. He remembers the near calm of it: Late at night, with the building as quiet as it was going to get, he wedged between the thin mattress of his top bunk and the hard concrete of the ceiling. If he bent his legs as he read, his knees nearly touched the ceiling.

But Andrisse blocked out the closeness of the space as he read. Instead, he turned on his nightlight and, sometimes for hours, absorbed scientific terms and imagined the process by which glucose gets absorbed or not.

“I fell in love with science and medicine in my prison cell,” says Andrisse, now assistant professor of physiology at Howard University College of Medicine in Washington, DC. “I spent hours and weeks just breathing it.”

Prison is where Andrisse started to plan for a different future for himself. “I’m going to be a doctor when I get out, man,” he remembers telling an incarcerated friend.

Today, Andrisse’s journey is still rare in academia. But he hopes it won’t be for long. As Americans increasingly question police behavior toward Black citizens, Andrisse spends his time building a bridge between his former life and his current one by mentoring both undergraduates and formerly incarcerated people.

From Ferguson to Physiology

There is a one-mile stretch of road that passes through Ferguson, Missouri, and four other municipalities in St. Louis County, each with its own police department. As a child growing up in that section of St. Louis County, Andrisse said he watched his siblings, his parents and others get pulled over, sometimes in every single town, racking up hundreds of dollars in fines.

Not knowing that the city had a policy of raising money by issuing tickets, and that the law had changed to allow police to search people at will under “stop and frisk” policies, Andrisse says he could only conclude that there were so many police officers in his neighborhood because “the folks here must be criminals.”

When he read a 2015 U.S. Department of Justice report on policing in Ferguson, after Michael Brown’s murder by police and subsequent protests, he wasn’t surprised to see that, actually, police had violated citizens’ Constitutional rights.

“Many officers appear to see some residents, especially those who live in Ferguson’s predominantly African American neighborhoods, less as constituents to be protected than as potential [offenders] and sources of revenue,” the report states.

What it meant for Andrisse is that he can’t remember a time when the police didn’t try to intimidate him. “I can recall being 8 years old and getting pushed around by cops in my neighborhood,” he says. He became an expert at talking the police down because he knew “they were going to come at me, assuming I was guilty of something.”

But Andrisse was smart and quick on his feet, mentally and physically. His family joked that he’d be a lawyer one day because he was so good at persuasive speech. His moves on the football field landed him a scholarship to Lindenwood University near St. Louis. There, he made the connection that would lead him to physiology.

Physiology by Night Light

That connection was Barrie Bode, PhD. When Andrisse met him, Bode was a professor of biology at St. Louis University and Andrisse was a college senior looking for a summer internship so he could “try to figure out what I was going to do with my life after college.”

But while he was applying for internships and attending football practice and classes, he was also the subject of a court case for dealing drugs. By the time he entered college, he had already been in the school-to-prison pipeline for years. According to the Justice Policy Institute, the school-to-prison pipeline consists of zero-tolerance policies at school, inviting in police officers who disproportionately target Black and Hispanic children, leading them to enter the juvenile justice system. Andrisse was facing a three-strikes rule that would send him to prison for 10 years to life. No one in his regular life knew, including Bode, who had just written a letter of recommendation for Andrisse to intern in his lab.

Andrisse was afraid to ask Bode directly for a character reference for his court case—he didn’t want those two worlds to meet—so he tucked the letter Bode wrote into his court files. That’s how Bode received a call from the prosecutor. Bode responded by writing a letter to the court and testifying on Andrisse’s behalf. “It felt really good that someone didn’t see me as a criminal,” Andrisse says.

Despite that reference, Andrisse received the minimum sentence of 10 years. During his sentence, Andrisse’s father died from uncontrolled diabetes—first, he lost a foot, then one leg, then the other. Grief-stricken, Andrisse studied photos of diabetic necrosis. He asked Bode to send him review articles on the pathophysiology of diabetes. By phone, Bode translated the language of physiology into lay terms.

Those articles became the primary excitement in Andrisse’s life. It was worth the guards shining a light in his face at night to startle him away from his article. It was worth an incarcerated friend shaking his head at Andrisse’s post-incarceration plans, saying, “Let’s go hit the weights. You’re thinking crazy again.”

“I knew I was about to be exploring new places in my head that would get me out of prison,” he says. “I would be inside that cell—a human cell and not a prison cell.”

Gaining Confidence

As the articles continued to come, and Bode continued to discuss them with him, something else happened. His thinking changed. He was starting to believe in himself.

He took that confidence with him when he was released from prison a few years later. Quickly, he earned a master’s degree in business administration from Lindenwood University and immediately started his PhD in physiology at St. Louis University. But it almost didn’t happen. When he was applying for the PhD program, he was asked: Had he ever been convicted of a felony?

Suddenly, that old feeling was back—of being pushed around by cops as a kid, of being pulled over one block after the next, of being talked about by the district attorney as a criminal mastermind. He felt like he would only ever be a person in a cell in most people’s eyes. “It’s a gut-wrenching feeling of ‘this place doesn’t want me.’ All the places I applied to asked that question, and all of them rejected me, except St. Louis University,” he says. “I had someone advocating for me.”

Bode was now on the acceptance committee at the university. He vouched for Andrisse, paving the way for his research into medications that might mimic the physiological benefit of exercise for people with type 2 diabetes. In four years, Andrisse completed his PhD and went on to Johns Hopkins University as a postdoc—Johns Hopkins doesn’t ask about applicants’ criminal history. After that, he served as an adjunct assistant professor of physiology at the university.

“Considering that I completed my PhD at the top of my class and in much less time than my peers, I was probably good enough to get in to all those other programs,” Andrisse says. “It’s a pretty safe assumption to say that it was probably because of me checking that [felony conviction] box that I didn’t get in and the fact that I was seen as a criminal.”

That’s why Andrisse testified before Maryland legislators in 2017, advocating for the state to ban the question on initial applications for college admissions. The ban went into effect in 2018, after the Legislature overroad the governor’s veto. In 2020, the Legislature banned asking about a criminal record on job applications before the the first in-person interview for businesses with 15 or more full-time employees.

Mentoring Others

Today, Andrisse continues to study the physiology of insulin resistance. But now, he’s doing something else he’s passionate about: mentoring. He and his friend Jerry Moore III—the one who had told him to stop “thinking crazy” about being a doctor after prison—started From Prison Cells to PhD (www.fromprisoncellstophd.org), where they mentor and work with formerly incarcerated adults to help them achieve their academic and professional goals.

The organization serves hundreds of people in 22 states, funded through a $5.2 million grant from the National Science Foundation, among others. It has a 97.5% post-secondary education matriculation rate. All of the organization’s mentors are formerly incarcerated. Andrisse still opens every new cohort of participants by telling his story.

“The system” is why there are not more like Andrisse. “I’m not a rare exception,” he explains. “There are many exceptional people in prison, but they lack access and opportunities. Talent is distributed evenly but access and opportunity are not.”

At Howard University, he counsels his students on the importance of the different kinds of mentors in their lives, such as the principal investigators who are coaches, showing you how to do better science through experience, and the sponsors, who can make connections for you and champion your work.

What he knows now is that he may have fallen in love with science in that prison cell, but he found his calling in mentoring. “What I want to do is help build the next generation of Black and Brown scientists.”

“I’m not a rare exception. There are many exceptional people in prison, but they lack access and opportunities. Talent is distributed evenly but access and opportunity are not.”

Stanley Andrisse, PhD