Think Like a Physiologist

The next generation of physiologists, doctors and researchers will come from the classes these passionate educators teach.

By Heather Boerner

Katie Johnson, PhD, knew she was doing her job right when her college students swore at her, just a little. She’d warn them about it on the first day of the semester: There’s going to be a time, she would say, when you’re going to come to me for help, and I’m going to tell you to go back to your group or look for the answer in another place.

“You’re going to spin on your heels, and swear at me under your breath, and you’re going to go back to your group and say, ‘She wasn’t helpful at all!’” she remembers telling her students. “Just realize: That’s the moment you’re learning to learn. That frustration, that thing you’re trying to get over, that’s what I’m trying to coax out of you.” Johnson is an independent education consultant and former chair of biology at Beloit College in Wisconsin.

Learning to learn—it’s a foundational skill for any work in the sciences. And watching it happen, and learning new ways to make it happen, has turned out to be just as compelling as working through a mechanism of action in the lab, say the physiology educators interviewed for The Physiologist Magazine. In science, deciding to focus on education is sometimes considered nontraditional, an unintentional choice. But for these educators, this is not the story at all. As APS launches the Center for Physiology Education this summer, we asked member-educators to share their passion for physiology, for education and for continuing to learn themselves.

The Hands-on Learner

Chris Trimby, PhD, assistant professor of physiology at the University of Delaware, still remembers his learning about Alaska becoming a state in grade school. That’s not because of an abiding love for the 49th state, but because he built a paper-mache relief map of the country’s most northerly state for a third grade project, complete with the Alaska Mountain Range, the Yukon River and the Aleutian Islands drifting off into the Bering Sea. He learned the same things he would have learned had he written an essay, he says, but he doubts he would remember an essay decades later.

Although Trimby had expected to be an engineer when he grew up, his first year in college changed his mind.

His introductory engineering classes were nothing like making that relief map of Alaska. They were dry and frustratingly theoretical. And they didn’t stay with him, either.

Although Trimby had expected to be an engineer when he grew up, his first year in college changed his mind.

His introductory engineering classes were nothing like making that relief map of Alaska. They were dry and frustratingly theoretical. And they didn’t stay with him, either.

“As I learned about teaching down the road, I was like, ‘Oh right, that’s why I got out of engineering,’” he says of how alienated he felt by those professors’ teaching styles. But it was a gift, he says, because it got him into a class where he learned to make bacteria glow in the dark to explain human genetic concepts. OK, now this was cool. This he could get into.

That’s how he ended up as a PhD student in a traumatic brain injury lab, developing viral gene tools to help treat and investigate those injuries. There, a faculty member was looking for help teaching a section of his applied physiology course. No one was taking him up on it, so eventually Trimby agreed. Suddenly, he got to be the one making the theory real for students. He was hooked. He was still interested in using gene therapy to cure cancer. But now he realized he could have an impact in another way.

“If I teach tens of thousands of students over my career, maybe one of them will get there,” he says. “I’m on that same path. I’m just taking a wider view of it.”

Today, Trimby continues to find creative ways to engage students. In a science fiction and biology course he designed, for instance, students create a hypothesis for how fast a Tyrannosaurus rex ran and back it up with morphometric and physiological references. In another course, students read “Blood Work: A Tale of Medicine and Murder in the Scientific Revolution,” a popular science book on the first blood transfusion in 1667, while learning about the physiology of oxygen transport in the blood.

“As a biology undergraduate student, you probably know more about how the human body works than this doctor did in the 1660s,” he tells his students. “There’s all this stuff swirling around the science. Oftentimes, it’s mostly happening in the lab. But that doesn’t mean it’s a smooth linear course or a coherent process. It’s ridiculous.”

Trimby likewise likes a challenge. And he gets it in teaching and designing curriculum. “I’ve seen multiple generations of students over my 10 years, and already things have changed very much in how we approach topics,” he says. “That keeps me motivated because it’s different. It’s not the same students every semester. They’re not a fixed quantity. The material is not a fixed quantity. It’s always changing. And that keeps it fresh.”

The Common Thread

Growing up in San Diego, Alice Villalobos, PhD, spent hours peering into tide pools, petting calves at the San Diego County Fair and watching whales migrate off shore. She’d marvel: All these animals, perfectly adapted to their environments, thriving no matter where they lived.

Over time, Villalobos started to see that common

thread in other parts of her life, like in the way her Mexican American culture was different from that of her Anglo friends but just as valid. It’s a philosophy that’s found its way into not just her comparative physiology work, but also

into how she teaches her physiology students at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center in Lubbock.

Over time, Villalobos started to see that common

thread in other parts of her life, like in the way her Mexican American culture was different from that of her Anglo friends but just as valid. It’s a philosophy that’s found its way into not just her comparative physiology work, but also

into how she teaches her physiology students at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center in Lubbock.

“You don’t assume differences are wrong. You assume differences are just simply different but still facilitate success—otherwise they wouldn’t continue,” she says. “So maybe a student is quirky, or maybe an animal isn’t a mammal like a white rat; they’re a chicken or a penguin. You observe the difference, appreciate it, embrace it and learn from it.”

When Villalobos landed at Blinn College in Bryan, Texas, it was like coming home. Sure, she had worked with students before. But now she was specifically teaching anatomy and physiology. Soon, to explain load pressure on the aortic valve, she would push against the closed classroom door on one side, asking students of various strength levels to try to push the door open from the other side. Or, she would find herself explaining how a shark’s choroid plexus—an organ in the brain that produces cerebrospinal fluid—is flat with epithelia on one side, while mammals’ choroid plexus has epithelia on both sides. And don’t get her started on the physiology of a desert kangaroo rat’s kidney versus that of a rain forest-dwelling animal. Still, years into her teaching career, she lights up at the thought of teaching it.

“If you’re smart, you really should be able to explain physiology to the average person, and you shouldn’t dumb it down,” she said. “Eventually, we all have to understand it in the exact same way. But how we express it can vary.”

The Builder

Adrienne P. Bratcher, PhD, jokes that she was a “sneaky and nosy” kid: sneaky because she would pilfer the anatomy and physiology textbooks from the desk where her mom was studying to be a nurse; nosy because when her mother’s best friend, Auntie Mamie, had open heart surgery when Bratcher was around 10 years old, Bratcher needed to know all about it, to the point of shadowing Auntie Mamie’s surgeon.

And while she thought she’d be a cardiovascular surgeon when she grew up, she realized early on that

her desire to learn why and how changes happened in the heart mattered more to her than doing surgery on humans. Still, she tells friends that she did achieve her childhood goal.

And while she thought she’d be a cardiovascular surgeon when she grew up, she realized early on that

her desire to learn why and how changes happened in the heart mattered more to her than doing surgery on humans. Still, she tells friends that she did achieve her childhood goal.

“When I entered a PhD program in cardiovascular physiology, I did the same surgeries on rats and mice that they do on humans,” says Bratcher, assistant professor of biomedical science at the Kaiser Permanente School of Medicine in Pasadena, California. “It’s always been a science road. It just went through a couple of windy towns, some highways, some interstates.”

Indeed, teaching was never on her radar. She just knew she loved science and wanted to do some good. But then as a doctoral student she found she had a talent for explaining to others the science she was so passionate about. And more than that, teaching and then mentoring allowed her to remain steeped in science while also adapting to every student, every class and every subject.

Instead, she says teaching gives her a chance to help students identify what they’re passionate about—like the high school football star who wanted to be a dentist, or the medical students who may find their passion in physiology. Today, as a professor at a new medical school, she says she’s become passionate about something new: developing courses to help other educators be better teachers.

“I just love creating,” she says. “I’m still that surgeon. I’m still the one wanting to put things together. So now I don’t call myself a surgeon. I’m a builder—a science builder.”

After all, she says, “Science is the gift that keeps giving.”

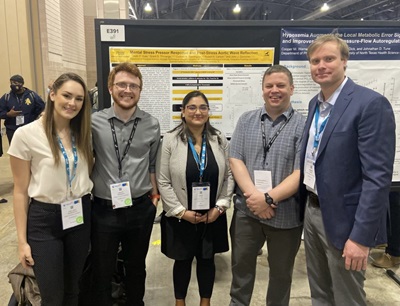

The Perseverant One

John Durocher, PhD, likes to start his classes at Purdue University Northwest in Indiana not with physiology but with history—his history. Durocher is now the Nils K. Nelson Associate Professor of Health Studies, with 25 publications under his belt, and leading the university’s Integrative Physiology and Health Sciences Center. But in the early 2000s, he was a first-generation college student who drove 100 miles many weeks to the Northern Michigan University campus from his job as a logger in Houghton, Michigan. And that was just one of five jobs he held at one time as he worked to complete his education.

“I try to become relatable,” he says, noting that 60% of his current students are first-generation college students and most of them work while attending school.

“I let the students know I’ve gone through some struggles so that they know that if they tell me something, I can understand. I want them to know I care.”

“I try to become relatable,” he says, noting that 60% of his current students are first-generation college students and most of them work while attending school.

“I let the students know I’ve gone through some struggles so that they know that if they tell me something, I can understand. I want them to know I care.”

Durocher’s path to teaching was unconventional. He wasn’t exactly an engaged student in high school, preferring mountain bikes and hockey to classwork. His first attempt at college didn’t take, and it wasn’t until he returned to college a few years later that he decided to turn his love for exercise into a physical therapy degree. But to get there, he had to get through anatomy and physiology first. He didn’t expect that would be where he’d stay.

“I fell in love with it immediately,” he says. “I couldn’t get enough.”

Suddenly, the kid who was indifferent to school was an adult who “could not wait to go to class.” Then, just as he was doubting he could really stick with school long enough to get a PhD in exercise physiology, his professor at Michigan Technological University walked past him in the anatomy lab and asked, “Would you like to be an undergraduate teaching assistant in the lab next year?”

“That was the life-changing experience,” he says. Suddenly, he was in charge of students, guiding them in their studies, and doing with them what his mentor had done with him: sharing, in a very practical way, why the body does what it does and why it matters.

Today, Durocher is still very active in research, working on studies on blood pressure regulation and in areas such as meditation and exercise. But he also has another passion: telling those students how he got where he is today and helping them get to their maybe unexpected futures, too.

“It’s gratifying training future health care professionals so that they have practical skills they can take into nursing or medicine or physical therapy,” he says. “And hopefully they find that love for anatomy and physiology along the way.”

The Lightbulb Moment

Johnson, the education consultant, was always good at identifying changes in chemical reactions and figuring out the mass of molecules using Avogadro’s number. But for her, early science education wasn’t just about the molecules and how they bonded. It was the people. When her tough-as-nails high school chemistry teacher showed her that women could be scientists, Johnson thought she might have more options. When her college professor, another woman, pulled her aside and told her, “Science is where you need to be,” she realized it was true.

Even when she was looking for PhD programs after college, Johnson chose the molecular physiology and biophysics

program at Vanderbilt University because, during a recruitment poster session, she got a good feeling when talking with her eventual lab mates, even though physiology was a huge transition from chemistry.

Even when she was looking for PhD programs after college, Johnson chose the molecular physiology and biophysics

program at Vanderbilt University because, during a recruitment poster session, she got a good feeling when talking with her eventual lab mates, even though physiology was a huge transition from chemistry.

“This group seems supportive,” she remembers thinking. “They talked to me like I was a person.” Plus, the lab had sent many graduates into industry, which is where she wanted to be.

But as she was finishing her PhD, her father got sick and she started to search for jobs closer to home. She interviewed for postdoctoral posts but had to admit to herself that she needed a break from constant lab work. Then she saw that her alma mater, Beloit College, was looking for a visiting professor to teach physiology. She emailed her old college professor for intel. A few months later, she was covering for that professor who was now on sabbatical.

Before Johnson knew it, she was standing in front of a class of first-year college students buzzing with the excitement of new classes and new peers. Although terrified, her focus grew clear. She realized she had this feeling before, standing at center court for tip-off as a collegiate basketball player. The energy of the crowd was feeding her now, just as it had done in her athletic career.

Then she started talking. And explaining. And students started to respond. Now it wasn’t just a lecture. It was a conversation, one where, slowly, she started to see the ideas click into place in the students’ heads.

“I fell in love with it,” she says. “It was amazing.”

Suddenly, her love of people and of science came together. This was what she was meant to do, she says. She stayed at Beloit for 11 years, moving from visiting professor to associate professor to chair of biology, and from studying the endocrine system to studying how to teach physiology better. Today, she is the founder of Trail Build LLC, which helps academic institutions and professional societies implement evidence-based teaching programs, with an emphasis on STEM and creating educational programs that prioritize equity, diversity and inclusion.

“It’s all about students,” she says, “and being part of their journey.”

This article was originally published in the May 2022 issue of The Physiologist Magazine.

“If you’re smart, you really should be able to explain physiology to the average person, and you shouldn’t dumb it down. Eventually, we all have to understand it in the exact same way. But how we express it can vary.”

Alice Villalobos, PhD

The Physiologist Magazine

Read the Latest Issue

Don’t miss out on the latest topics in science and research.

View the Issue Archive

Catch up on all the issues of The Physiologist Magazine.

Contact Us

For questions, comments or to share your story ideas, email us or call 301.634.7314.