Post Postdoc

How to be successful as a new faculty member and collaborator.

Each issue, we ask

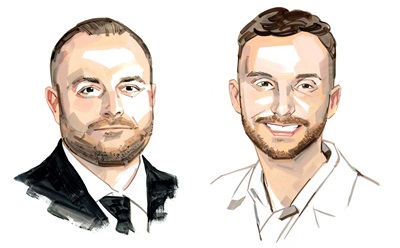

a trainee or early-career member to pose their career questions to an established investigator and mentor. Here, Justin Sprick, PhD, an assistant professor at the University of North Texas, asks Frank T. Spradley, PhD, an associate professor and the

director of basic research in the Department of Surgery at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, for advice on being a new faculty member.

Each issue, we ask

a trainee or early-career member to pose their career questions to an established investigator and mentor. Here, Justin Sprick, PhD, an assistant professor at the University of North Texas, asks Frank T. Spradley, PhD, an associate professor and the

director of basic research in the Department of Surgery at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, for advice on being a new faculty member.

Q: What are some of the common pitfalls that you see junior faculty make when starting their first

tenure-track position, and how do you avoid them?

A: It is very easy to get overwhelmed with the ever-increasing volume of administrative tasks asked of you. It is important to understand when to say no and focus on those tasks that are most important.

For example, if your gut is telling you to write a grant, then that’s your answer. Form a mentoring team that will help you focus on achieving career checkpoints, making sure to include sponsors that can nominate or advise on optional tasks that

will help, not hinder, you.

Q: “Team science” and multiple-principal investigator (PI) grant submissions are becoming more common as the problems we face often require a multidisciplinary approach to solve. What tips do you have

for successfully initiating new collaborations to ensure that expectations are clearly established and both parties benefit?

A: This is a very important point. Most departments and centers should have work-in-progress meetings that bring together

basic and clinical researchers. This is the case for our Cardiovascular-Renal Research Center and is the reason I am now involved with several co-PI grants. Attending these meetings, as well as national/international conferences, is the best way to initiate

such collaborations—more specifically, get up, state your name and ask a question!

Once the team is established, meet often (the beauty of virtual meetings) to set deadlines. The best way to flesh out an outline of expectations is by writing grants because you plan experiments for years in the future. Once funded (fingers crossed!), you will most likely be expected to submit progress reports to the granting agency that effectively reinforce that everyone is meeting goals. Most of the data generated will likely be submitted for publication or used as preliminary data for future grants, so it is vital at the get-go to talk about authorship.

Q: With technological advances, many of the experimental techniques we have spent

years mastering will eventually become less common or potentially even obsolete. As a trainee, we spend much of our time in the laboratory developing our technical skills. As faculty, however, this is often not possible due to competing demands on our

time. How do you determine where to draw the line regarding taking the time to learn a new experimental technique versus seeking collaborations with others who already have the technique established?

A: I gather you understand what I meant about

the “ever-increasing volume” of requests on our time mentioned in answer one above. Sure, the research tool belt that is developed during one’s training will need to be realigned as science advances, which could involve using your knowledge

base in a manner to teach your lab how to use a new piece of equipment (by understanding what final outputs should be) or range to the development of experimental animal models mimicking human disease (by reinforcing that every observational change in

physiology and keeping good notes are critical).

I don’t think that anything learned—even basic lab skills such as note-taking and critical thinking and review—are never not useful. However, they should be modified for instructional purposes to train your research staff and students. Then, the expectation is that they will free your time by becoming the teachers themselves. Of course, you can provide guidance, but grants and manuscripts must be written and reviewed to staff said research team.

Such computer work will lessen your time to learn new hands-on techniques, but assembling a group of researchers that want to learn and work well with others, including your intramural and extramural collaborators, is key to allow time for all aspects of scientific discipline. Learning to interview for these positions is a topic for an entire conversation in itself.

Got a career question you'd like to submit? Email it to tphysmag@physiology.org. We may use it in an upcoming Mentoring Q&A.

The Physiologist Magazine

Read the Latest Issue

Don’t miss out on the latest topics in science and research.

View the Issue Archive

Catch up on all the issues of The Physiologist Magazine.

Contact Us

For questions, comments or to share your story ideas, email us or call 301.634.7314.