The Physiologist Magazine

Read the Latest Issue

Don’t miss out on the latest topics in science and research.

Contact Us

For questions, comments or to share your story ideas, email us or call 301.634.7314.

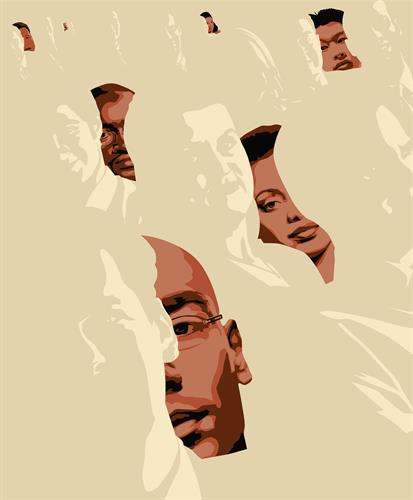

An Eye on Diversity

Universities share their diversity and inclusion initiatives that others can learn from.

By Candace Y.A. Montague

When Keren Herrán was 16, she attended the Hispanic Heritage Youth Awards in support of her older brother, Zuriel. The keynote speaker was physiologist Teresa Ramírez, PhD, a then-postdoctoral fellow at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (Ramírez is a member of the American Physiological Society and is now the Society's member communities manager.) Herrán was impressed and inspired by her speech. She told her aunt sitting next to her that she wanted to meet this Latina who was the first face in science she ever saw that looked like her.

“Hearing her express her experience as a first-generation Latina and her passion for giving back to the community and how she enjoys being in science as a minority inspired me,” Herrán says. Her aunt insisted she approach Ramírez after the ceremony. From there, a mentor relationship was formed. Herrán credits Ramírez with helping her with many things, including completing college applications. “She has been like a big sister to me. She is a very big part of my life.”

Herrán is now a senior at University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC), studying public health. She’s excited about where she has landed after high school but admits it can be daunting to be a minority in a field where Hispanic students are few and far between. “You must work double hard to prove that your upbringing and background is not something that makes you less of a scientist. I am proud of my background, upbringing and culture, recognizing the value they add to my intelligence and skill sets, thus enhancing my professional pursuits.”

The need for diversity in science has never been greater. But decades of racism and discrimination have created a divide that will not be easy to close. It will take more than a few book club readings to make a real impact on education and the workforce. What are the best practices for bridging the gap and getting everyone to truly buy into equity? During this moment of racial reckoning, when more academic institutions are turning their attention to diversity, equity and inclusion, we asked several institutions with successful diversity programs how they are succeeding and what their tips are for other institutions to follow.

High expectations and group support

Interest in science as a field of study has remained steady among minority students in the past 25 years. According to the National Science Foundation’s STEM Education Data, in 1995, 35% of Black college freshmen and 37% of Hispanic college freshmen had plans to major in science and engineering when they entered undergraduate school. By 2012, Black students’ intentions rose slightly to 36% while Hispanic students’ intentions increased to 41%.

Herrán credits her success to the Meyerhoff Scholars Program, a UMBC program aimed at enrolling and supporting minority students in STEM studies. As a participant, she was connected with a network dedicated to helping her and her cohort with STEM fields through tutorials, enrichment activities, peer assistance and mentorship. Robert Meyerhoff and Freeman Hrabowski, PhD, began the program in 1988 as a scholarship program for Black men. The following year, women were admitted into the program. Today, the Meyerhoff Program has graduated more than 1,100 minority students who have gone on to attain master’s and doctoral degrees.

Hrabowski, UMBC president, explains that high expectations and group support help students in the Meyerhoff Program avoid falling through the cracks. “We put a lot of emphasis on tutorial efforts, group study, use of technology and transparency in the work,” he says.

He describes the program as “intrusive.” Instead of just asking the students how they’re doing, the program keeps track of the students’ grades and progress. “And for the students who are not doing well, we look into tutorials to get their grades up,” he says.

The program has been so successful at graduating minority students in STEM that it has been replicated at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Penn State and Howard University.

Earnestine Baker, executive director emerita of the UMBC program, describes some strategies the program uses for student retention: “One part of [retention] is having the students realize the politics with getting advanced degrees in science. The politics are different. And sometimes one will not see it, but they feel it. You become a victim of the results, and the results may be ‘I can’t do this. I’m going to transfer.’ Students also deal with isolation, so we create an environment at the undergraduate level to prepare students to combat all these negative feelings.”

A deeper, more formidable obstacle in enrolling and keeping minority students in science is systemic racism. Black and Hispanic students face pervasive, tough challenges. “You can look at structural racism from several perspectives,” Hrabowski says. “One, the schools for Black children receive less funding and are not as strong academically. Many of these schools don’t give children strong reading skills. If you give me a child who can read, I can teach her to solve word problems. But if she doesn’t read well, I can’t teach her word problems or chemistry or physics. Two, there are fewer opportunities for Black and Latinx children to know what’s possible in science; they have fewer role models. So, this notion of structural racism and the academic achievement gap is very real.”

#BlackInTheIvory

Black and Hispanic students moving into graduate-level education may find themselves in unchartered territory. As undergraduates, they may have felt supported by fellow minority classmates and mentors. But graduate school is different and can often be isolating.

Awareness of systemic racism has been gaining steam over the past decade, and it has become prevalent on social media. Dexter Lee, PhD, associate professor in physiology and biophysics at Howard University College of Medicine in Washington, D.C., explains how the Twitter hashtag #BlackInTheIvory opened a dialogue about racism in science. “After the George Floyd murder, there was this tweet about African American encounters in science. More specifically, they talked about their training in grad schools across the country. Unfortunately, African Americans and other minorities are underrepresented. And oftentimes, there are encounters that are less than desirable. But there isn’t always a forum to discuss it,” Lee says.

Using the #BlackInTheIvory hashtag, Black researchers are publicly discussing the microaggressions—and sometimes, macroaggressions—they’ve had to overcome to pursue their dream careers in academia. “‘Black in the ivory’ brought back experiences that I’m not too fond of sharing,” Lee says. “But I think it’s important to shine a light on what many African Americans have endured while trying to get advanced degrees in science.

“I received fair, and even favorable, treatment from professors when I was in school some 25 years ago,” Lee continues. “As a graduate student and postdoc, I did not receive that same treatment from some students and postdoctoral fellows.”

Creating an equitable workplace

Students in STEM programs eventually become researchers, professors and leaders in the workforce. What challenges will they face that college did not prepare them for? Being Black, Hispanic or from other underrepresented groups in a predominately white workspace carries a level of weight that only minorities can understand. Minority scientists must handle unfair assumptions—such as colleagues assuming they got their jobs because of affirmative action or that they always serve as a spokesperson for their entire race. Researchers of color also have little recourse when a colleague takes credit for their work or ideas.

A 2018 Pew Research Center report shows that workplace diversity is considered important by the majority of employees in STEM and that Black and Hispanic employees considered diversity a high priority. Among those employed, 84% of Blacks, 64% of Asians

and 59% of Hispanics said racial and ethnic diversity in the workplace is extremely or very important compared to just 49%

of whites.

Black people in STEM reported more race-based discrimination than other groups. According to the report, 62% of Blacks, compared with 44% of Asians and 42% of Hispanics, in STEM jobs said they had experienced discrimination at work.

Experts say creating a diverse and equitable workplace is about implementing continuous opportunities for growth and learning in a safe space where uncomfortable conversations can be had. At the University of California, Davis, equity training is presented in various ways and on a rolling basis. Renetta Garrison Tull, PhD, vice chancellor of diversity, equity and inclusion, says in addition to encouraging staff to examine their own biases, they offer hands-on learning opportunities.

“We have faculty who are looking toward ways to make their climates not just equitable but welcoming,” she says. “So, there are groups of faculty members now that are engaging in anti-racism book readings and engaging in opportunities to learn together. They’re coming together to formulate their own committees on equity.”

The school has also implemented university-wide programs, including a film series for students and faculty, a workshop on transformative justice and a racial trauma website with faculty- and student-focused resources, news and guidance documents. (Visit https://diversity.ucdavis.edu/resources-racial-trauma.)

Building anti-racist leadership

At the University of California (UC) Merced, efforts to increase diversity include developing positions and training leaders to find and address racial inequities. Dania Matos, JD, associate chancellor of equity, diversity and inclusion, recommends that other college campuses develop a faculty equity adviser program. These advisers work with search committees to create a diverse candidate pool for hiring. They also work with hiring units to ensure that newly hired staff get acquainted with groups such as the critical race and ethnic studies faculty at UC Merced or women in STEM groups.

“We build active anti-racist leadership with the understanding of critical race theory (relationship between racial categories and institutional power),” Matos says. “For instance, ensuring they take data courses that equip them with the skills to uncover racial inequities within their institution and a course on facilitating conversations on race, racism, white supremacy and anti-Blackness. These are specific skill sets that form the choices you make daily and lead to becoming an actively anti-racist institution through the development of transformative practitioners.”

When it comes to creating an inclusive academic environment, it helps to think collectively. Consider everyone’s culture and background as something that will enhance growth, not hinder it. Experts advise not to be afraid to have honest, respectful

dialogue to keep the growth going.

Language Matters

This glossary of terms, defined by various racial equity education centers and resources, can be used when discussing the creation of equitable spaces.

Anti-oppression: Work that dismantles white supremacist forces that marginalize, silence or otherwise subordinate one social group or category. Practicing anti-oppression work in real terms is not only confronting individual examples

of bigotry, or confronting societal examples, it is also confronting ourselves and our own roles of power and oppression in our communities.

Anti-racist: An anti-racist is a person who is supporting an anti-racist policy

through their actions or expressing anti-racist ideas. This includes the expression or ideas that racial groups are equals and do not need developing, and supporting policies that reduce racial inequity.

Code switching: Moving back and forth between two languages or two dialects or registers of the same language based on who your audience is. Some people in marginalized groups resort to code switching to prove their intelligence. Others use it to identify with

the predominant social group. Code switching hides an individual’s culture and works against inclusion.

Diversity: Diversity has come to refer to the various backgrounds and races that comprise a community,

nation or other group. In many cases, the term not only acknowledges the existence of diversity of background, race, gender, religion, sexual orientation and so on, but implies an appreciation of these differences.

Equity: Promoting justice, impartiality and fairness within the procedures, processes and distribution of resources by institutions or systems. Tackling equity issues requires an understanding of the root causes of outcome disparities within our society.

Implicit bias: When we have attitudes toward people or we associate stereotypes with them without our conscious knowledge. Everyone carries implicit biases in their minds to some extent. In other words, implicit biases

are the “thoughts about people you didn’t know you had.”

Inclusion: This is an outcome to ensure those who are diverse actually feel and/or are welcomed. Inclusion outcomes are met when you,

your institution and your program are truly inviting to all—to the degree to which diverse individuals are able to participate fully in the decision-making processes and development opportunities within an organization or group.

Microaggression: The everyday verbal, nonverbal and environmental slights, snubs or insults—whether intentional or unintentional—that communicate hostile, derogatory or negative messages to target persons based solely

on their marginalized group membership.

Tone policing: Tone policing is when a person attacks the way someone says something in order to diminish the validity and importance of the statement. When people with privilege

feel uncomfortable, they may tone-police in an effort to silence someone belonging to a marginalized group.

Definition sources:

www.ibramxkendi.com

The Aspen Institute

https://dei.extension.org

American Bar Association

Perception Institute

Psychology Today

https://theantioppressionnetwork.com/what-is-anti-oppression

This article was originally published in the November 2020 issue of The Physiologist Magazine.

One part of [retention] is having the students realize the politics with getting advanced degrees in science. … You become a victim of the results, and the results may be, ‘I can’t do this. I’m going to transfer.

Earnestine Baker

Language Matters

This glossary of terms, defined by various racial equity education centers and resources, can be used when discussing the creation of equitable spaces.

UC Merced teaches its staff “specific skill sets that form the choices you make daily and lead to becoming an actively anti-racist institution through the development of transformative practitioners.

Dania Matos, JD