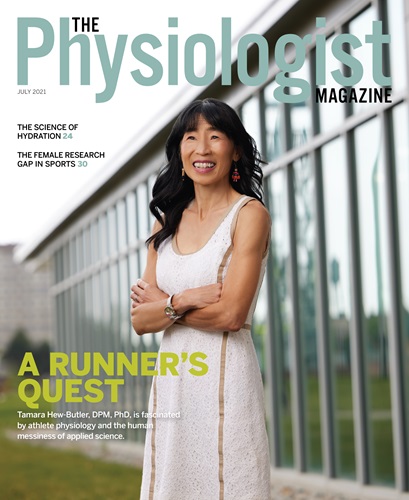

A Runner’s Quest

Tamara Hew-Butler, DPM, PhD, is fascinated by athlete physiology and the human messiness of applied science.

By Christina Hernandez Sherwood

Tamara Hew-Butler, DPM, PhD, was a Texas-based podiatrist specializing in runners in January 1999 when she volunteered as assistant medical director of the Houston Marathon. A marathoner herself, Hew-Butler watched a surge of inexperienced athletes thunder past the medical tent that mild morning, some downing dozens of cups of water during the 26.2-mile race. When ailing runners came to the medical tent, they were treated with intravenous fluids. “We assumed everyone was dehydrated,” Hew-Butler says.

But by the end of the day, four runners had had seizures and were transferred to the hospital in weeklong comas. The diagnosis: critical hyponatremia, a dangerous condition characterized by low blood sodium. The Houston marathoners all recovered, but three years later Hew-Butler saw hyponatremia in the headlines. In 2002, the condition killed two young athletes, a 28-year-old woman running the Boston Marathon and a 35-year-old woman competing in the Marine Corps Marathon in Washington, D.C.

“That set me off on this quest,” Hew-Butler says. “I needed to know why these runners were dying, whether this was because they were drinking too much water or they didn’t replace their salt.”

So, in a gamble that paid off big, Hew-Butler quit her job of nearly a decade and moved to South Africa to study with Timothy Noakes, MBChB, MD, DSc, the renowned sports scientist who first reported on hyponatremia in the 1980s. As she earned her PhD in physiology, Hew-Butler learned that the condition, while uncommon, is completely preventable. “All of our research pointed toward people just drinking way too much water,” she says. “That’s how I got into overhydration.”

A decade and a half later, overhydration is still Hew-Butler’s first physiological love (her Twitter handle is @hyponaqueen). In May 2021, she published an article in The Washington Post warning that the conventional wisdom of eight glasses of water a day isn’t right for everyone. “Not to burst anyone’s water bottle,” she wrote, “but healthy people can actually die from drinking too much water.” (See “The Science of Hydration” on page 24.)

Hew-Butler’s

research interests have expanded since she joined Wayne State University in Detroit, where she’s now an associate professor of exercise and sport science. “The PhD in physiology gives you an understanding of how the body works and how to investigate

the problems that come up,” she says. “That’s really the take-home. Now my research has spun out in a lot of different directions because that’s where I landed.”

Hew-Butler’s

research interests have expanded since she joined Wayne State University in Detroit, where she’s now an associate professor of exercise and sport science. “The PhD in physiology gives you an understanding of how the body works and how to investigate

the problems that come up,” she says. “That’s really the take-home. Now my research has spun out in a lot of different directions because that’s where I landed.”

Growing up in Los Angeles as the second daughter (or “the son that my dad never had”), Hew-Butler was a wannabe gymnast who cheered for her home teams, especially the NBA’s Lakers and the NFL’s Rams. She took up running at the University of California, Los Angeles, in her undergraduate years—during that tricky transition into adulthood when people are at risk of developing a sedentary lifestyle. She eventually settled into a routine of running three miles a day. “That’s the one constant that’s been through my life,” she says. “When I don’t run, my body is not used to that. Everything hurts.”

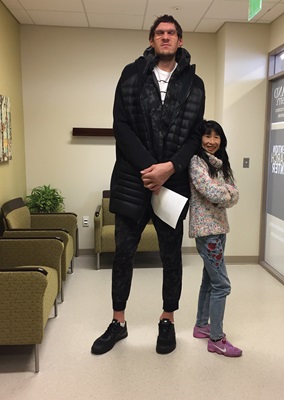

Hew-Butler is fascinated by athletes. She screens student-athletes, noting their body composition, mental health and other markers, then tracks changes to learn how training and competing affects them. Her latest fixation is the fine line between peak athletic performance and overtraining. She also tracks professional athletes to learn more about what happens when that elusive line is crossed.

“When people overtrain their performance gets worse. They become extremely fatigued. They get sick all the time. They have headaches and brain fog, and their body is not functional anymore,” Hew-Butler says. “Once you get there, it’s years before you get better, if you get better at all.” In that way, she adds, overtraining is a mysterious illness like chronic fatigue syndrome or long COVID-19.

As the pandemic shut down Wayne State last year, Hew-Butler went to work studying the impact of the lockdown on the performance of college athletes. Her preliminary work with the university swim team found that while the athletes spent about half the normal time training in the pool, sprinters actually performed better post-quarantine. The distance swimmers, however, didn’t fare as well.

Hew-Butler, who considers herself “a weird outsider” in the world of physiology, relishes the human messiness of applied science. One of her favorite studies, on sodium balance in runners participating in a 100-mile race, involved tracking their food and drink intake, then collecting their labeled bags of urine from along the course to study in the lab. “That’s the physiology that’s more real life,” she says. “We can’t control it.”

When she’s not studying athletes, Hew-Butler tries to create more of them. Part of her mission, she says, is to “inspire the joys and benefits of regular, lifelong exercise.” In one example, her research team ran a three-month trial in which obese college students were trained to run a 5K Turkey Trot. “They had more energy, and it inspired them to keep going,” Hew-Butler says. “Anything that we can do from a preventive health standpoint is important. It’s important for the health of society, but I think there are a lot of benefits that people don’t realize.”

Once it’s safe to go back into the field, Hew-Butler wants to expand her lab’s

reach off campus. She’s writing grants to fund a project in which students would establish fitness centers (think CrossFit “boxes”) to provide workout equipment, classes and training plans throughout Detroit, where more than two-thirds

of the population is overweight or obese. The idea is to make it as easy as possible for residents to work out, Hew-Butler says. The goal is a host of self-sustaining gyms across the city. “We need that here in Detroit,” she says.

Once it’s safe to go back into the field, Hew-Butler wants to expand her lab’s

reach off campus. She’s writing grants to fund a project in which students would establish fitness centers (think CrossFit “boxes”) to provide workout equipment, classes and training plans throughout Detroit, where more than two-thirds

of the population is overweight or obese. The idea is to make it as easy as possible for residents to work out, Hew-Butler says. The goal is a host of self-sustaining gyms across the city. “We need that here in Detroit,” she says.

Like much of the rest of the world, Hew-Butler’s work life has largely been confined to her home since March 2020. But her home happens to be a 10-acre hobby farm 60 miles north of Detroit that she shares with her husband, Bill, and their two domesticated ducks.

“Growing up in LA, we never had space,” Hew-Butler says. “Here, there’s space everywhere. It’s like living in a park.” She goes for runs through the property and watches the ducks on the pond, while Bill tends to the garden and the apple, cherry and peach orchard. In summer they eat fresh tomatoes, and in winter they shovel fresh snow.

Still, Hew-Butler is eager to return to the lab—the pandemic shuttered it for a full year—and the classroom. “The students that I have, they’re hungry, and they work really, really hard,” she says. “It’s just so vibrant and happy and exciting. We learn stuff every day and we talk about it. To me, that’s what education is. Experimentation is part of your life. Whatever field you go into, you have to learn how to experiment.”

Her ongoing work includes a dehydration study that uses sensors, such as the Apple Watch, to monitor for subtle heart rate changes. Otherwise, Hew-Butler is waiting for the next big question that will guide her research. “At this point it’s like, what falls in my lap?” she says. “When the swimmers end up in the hospital, why did they get there? When the basketball players all get fractures, why did that happen? We see a problem and try to find a solution.

The Physiologist Magazine

Read the Latest Issue

Don’t miss out on the latest topics in science and research.

Contact Us

For questions, comments or to share your story ideas, email us or call 301.634.7314.

“We learn stuff every day and we talk about it. To me, that’s what education is. Experimentation is part of your life. Whatever field you go into, you have to learn how to experiment.”