Overworking Women

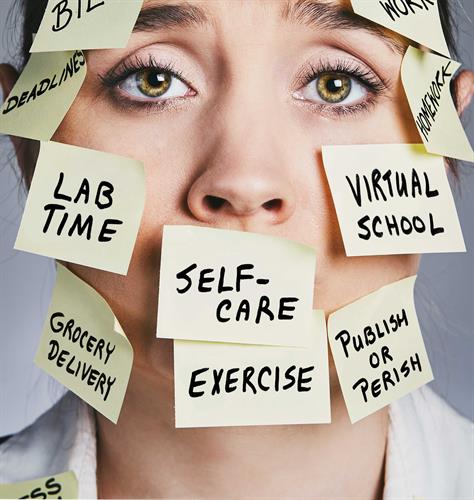

The work day for many women already stretched beyond 9–5. And then the pandemic hit.

By Christine Yu

When Gina Mantica returned to her lab at Tufts University in Boston in September 2020, it felt like a ghost town. Normally, there are always people around—postdocs, students, faculty—so she expected to see a few others in the building. Instead, during the COVID-19 pandemic, she heard and saw no one.

The more Mantica was in the lab, the more isolated she felt. Some days, she’d see one or two people from a safe distance in the hallway. When a new postdoc needed to observe her performing surgery on the zebra finches Mantica was studying, she operated in one room while the postdoc watched a video feed in another room and asked questions through the door. There was no longer a sense of community, and working alone compounded the solitude she already experienced from months of working from home.

Mantica was a fifth-year doctoral candidate in biology, studying animal behavior and physiology, and expected to complete her degree in December 2021. But when the pandemic shut down the university in March 2020, her research halted. Without lab access, she made no progress for six months, potentially adding an extra year to her studies.

It wasn’t just the lack of company. She didn’t feel her adviser and research faculty were supportive, nor that her school was providing clear guidelines—especially to students deep into their programs. How would the shutdown impact graduation timelines? Would students still be required to publish a specific number of papers? “It was a very different environment. Trying to figure out a lot of stuff on your own and trying to communicate with people when they’re on separate schedules was hard,” she says.

More than 2 million women dropped out of the labor force between February and October 2020, leaving the lowest percentage of working women in over 30 years.

Ultimately, Mantica decided to leave her program and is now the marketing communications specialist at the Rafik B. Hariri Institute for Computing at Boston University. “I love my research. I would have loved to finish it,” she says. “But I didn’t want to keep pushing myself if I wasn’t receiving the support I needed to succeed.”

One year into the pandemic, scientists continue to feel its effects. Some, like Mantica, have lost valuable research time at critical junctures in their career. For others, work has taken on layers of complexity, from pivoting to online learning to adapting to new workplace protocols.

Women, in particular, have felt the burdens acutely. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, more than 2 million women dropped out of the labor force between February and October 2020, leaving the lowest percentage of working women in over 30 years.

Between August and September alone, 865,000 women left the workforce—four times higher than the number of men, according to the National Women’s Law Center. Researchers have also found a decline in productivity among female scientists. Preliminary studies suggest that women submitted to preprint servers at a lower rate compared to men and experienced a dip in first authorship compared to 2019.

“Our male counterparts are still in the lab, publishing papers and getting grants,” says Adrienne King, PhD, assistant clinical professor in the School of Public Health at Georgia State University. “I’ve had to step back, be here for my family and take on different responsibilities.” And the long-term impact could be damaging for female scientists.

Changing Workplace Norms

COVID-19 has upended everyone’s lives, forcing many to rethink how they work. For Carrie Northcott, PhD, director and research lead for the Digital Medicine and Translational Imaging Group at Pfizer, work responsibilities exploded. Not only is there a greater interest in digital medicine, Pfizer prioritized COVID-19 vaccine development. As people shifted roles, Northcott assumed new responsibilities to cover for those who were redeployed. “While COVID is really important, we don’t want other areas to fall behind or be neglected,” she says. She’s also losing out on valuable in-person interactions. She can no longer pop in on collaborators either, instead relying on phone and video calls.

Alyssa Brown rejiggered her schedule so she could continue her research while minimizing the risk of infection. She’s a MD/PhD student, currently completing her PhD at Mayo Clinic in Minnesota before returning to the University of Louisville to finish the final year of her medical degree. She works normal business hours at home before heading to the lab in the evening when no one is around. While her hours aren’t longer than usual, it takes more mental energy. “Normally, I could just go in whenever. I wouldn’t have to think about what time I’m going in, what I need to prep and what I need to do while I’m there,” she says.

A Unique Set of Challenges

On the whole, women face uniquely difficult challenges. Prior to the pandemic, women shouldered the majority of household and caregiving responsibilities, even among couples who claim duties are evenly split. When the pandemic shifted life en masse into the home, and as schools, child care centers and facilities for the sick and elderly shut down, the demands on women’s time and labor grew exponentially.

“There’s a simultaneous ramping up of the work to be done and a destroying of the support that’s necessary for women to do that work,” says Jessica Calarco, PhD, associate professor of sociology at Indiana University. Women tend to perform a disproportionate share of the “care work” at institutions too, like serving as informal mentors and committee members on special initiatives, experts say.

Calarco points to policies that originated in the wake of World War II for differing attitudes toward women’s work in the U.S. compared to other countries. “Many Western European countries, especially those hardest hit by the war, put in place policies like universal child care and paid maternity leave that encouraged women to work and allowed women to stay engaged in the workforce,” she says. The U.S., on the other hand, didn’t need to rebuild or face a worker shortage. “The consequence was that the U.S. actively pushed women back home,” she says. The lingering effects of these policies can be treacherous as women juggle their career during unprecedented circumstances like a pandemic.

There’s a simultaneous ramping up of the work to be done and a destroying of the support that’s necessary for women to do that work.

Jessica Calarco, PhD

Take Northcott, for example. Her roles during the pandemic include mom of two, wife, teacher, germ warrior, grocery-order person and cruise director. She’s had to problem-solve—a lot—like programming her younger son’s schedule into Alexa to remind him to switch classes so she doesn’t have to. On a day when he was in tears because he couldn’t get into his online classroom, Northcott was on a teleconference. So, she helped her son connect to Zoom while simultaneously answering questions from colleagues. “You’re dealing with something that’s really important for work, but you also have your child there and you want to make sure he gets the support he needs as well. It’s tough,” she says. “There’s more stress, more anxiety and more things to get done. I think women don’t have a choice but to multitask.”

Burning the Candle at Both Ends

Lourdes Alarcón Fortepiani, MD, PhD, says she’s exhausted. When classes transitioned to remote learning in the spring, the professor at the University of the Incarnate Word in San Antonio scrambled to adapt her three courses to the new online environment.

It was overwhelming, and her workload more than doubled. She’d record classes at 3 a.m. while her family slept. During the summer, she typically teaches 60-plus students in a laboratory session. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, she had to host multiple small-group Zoom sessions at the beginning of summer. When labs reopened, she separated her typical two 30-student sections into six 10-student groups.

Working moms, in particular, have carried the heaviest burdens, often putting their own health and well-being on the line to remain engaged workers. With her husband working outside the home, Fortepiani’s the de facto caregiver and teacher while managing her full-time job. Often, she could not dedicate enough time to her kids. “It’s draining psychologically because I want to be there for them during the school day and I couldn’t,” she says. She continually readjusted her schedule to make time.

Calarco witnessed a similar tension in her research with mothers in southern Indiana. “When they feel like they’re failing both as workers and mothers, they internalize that sense of failure. They feel it as guilt that they’re not able to be the kind of mother they know their kids need right now and as frustration that they’re not able to be the kind of worker that their boss expects them to be or that their colleagues are able to be during the pandemic,” she says. “That’s not the case in other countries, especially those with less individualistic cultures and stronger social safety nets.”

With a three-year-old son at home, King, the Georgia State University professor, also feels she is burning the candle at both ends. “I don’t really have a work-life balance right now,” she says.

Overhauling and preparing her three classes for remote learning required considerably more time than normal, and King logged many early mornings and late evenings. “And these are undergrad classes so I’m the sole person teaching,” she says. King’s research has mostly been placed on hold since the summer. “It’s nowhere near the level of production prior to COVID,” she says. While she’s not at the bench, she’s still writing grants and analyzing data.

King also worried about how she would replace the education and interaction her son received outside the home. While schools provided learning materials to older children, King was left on her own. “I spent hours finding curriculums similar to what he would have been exposed to in school. I wanted to make sure he will be ready for pre-K in the fall of 2021,” she says.

Luckily for King, since August, she’s had help around the home. Twice a week, her mother takes over child care duties for a few hours so King can work. That additional help can be crucial, Calarco says. Her research found that women who have access to child care support—no matter their race, ethnicity or social class—seem to fare better than women who don’t have help.

Informal Work and Stress

It’s not just formal work responsibilities that are demanding women’s time. The scientists we spoke with also described taking on more informal roles. Fortepiani and King say students are equally stressed and require more check-ins and support, in addition to their regular advisory roles. “I try to convey to them that we’re all in this together; I’m not going to leave you hanging,” Fortepiani says.

For MD/PhD student Brown, most of her medical school friends are now second-year residents. “I worry about them getting sick and burnt out. I worry about new grad students because they’re not having the normal experience of making friends and having a group to hang out with during the long Minnesota winters,” she says. “I’m trying to check up on people and see if they are doing OK because you don’t get that visual, in-person check-in as often.”

Brown, who lives alone and describes herself as an extrovert, says the lack of social interaction has been hard at times. She’s coped with socially distanced walks and lunches with colleagues during the summer and virtual coffee dates with friends. Still, she worries. “I had anxiety and depression before the pandemic, and it’s made it worse,” she says. “I always wonder when we will shut down again. When will we have work-from-home orders? Will they try to move our animal facility again? Will they continue to let us use animals?”

The Upside

Despite the difficulties, scientists see glimmers of light in their experience. Northcott of Pfizer has marveled at the way the scientific field has pulled together. “We’re seeing collaboration across lines, both academic and industry, like never before,” she says. “The fact that we have a vaccine in a year is incredible.”

King and Fortepiani both noted that their relationships with students have improved as they’ve leaned on each other more. Several others pointed to new habits like daily walks and embroidery to help cope with the stressful times.

And despite leaving her PhD program, Mantica loves her new job in science communications, something she’s always wanted to do. She hopes that the pandemic will lead employers to rethink how they support employees so “there isn’t this exclusionary aspect to working if you’re a mom, trying to start a family or have more household responsibilities.”

Without efforts to support female scientists at all levels—from the research community to academia to employers—the future of science could look very different.

The Physiologist Magazine

Read the Latest Issue

Don’t miss out on the latest topics in science and research.

Contact Us

For questions, comments or to share your story ideas, email us or call 301.634.7314.

I don’t really have a work-life balance right now.

Adrienne King, PhD