The Future of Women’s Heart Health

Despite progress, women remain underdiagnosed and undertreated for heart disease. Physiologists are working to change that through groundbreaking physiology research.

By Isobel Whitcomb

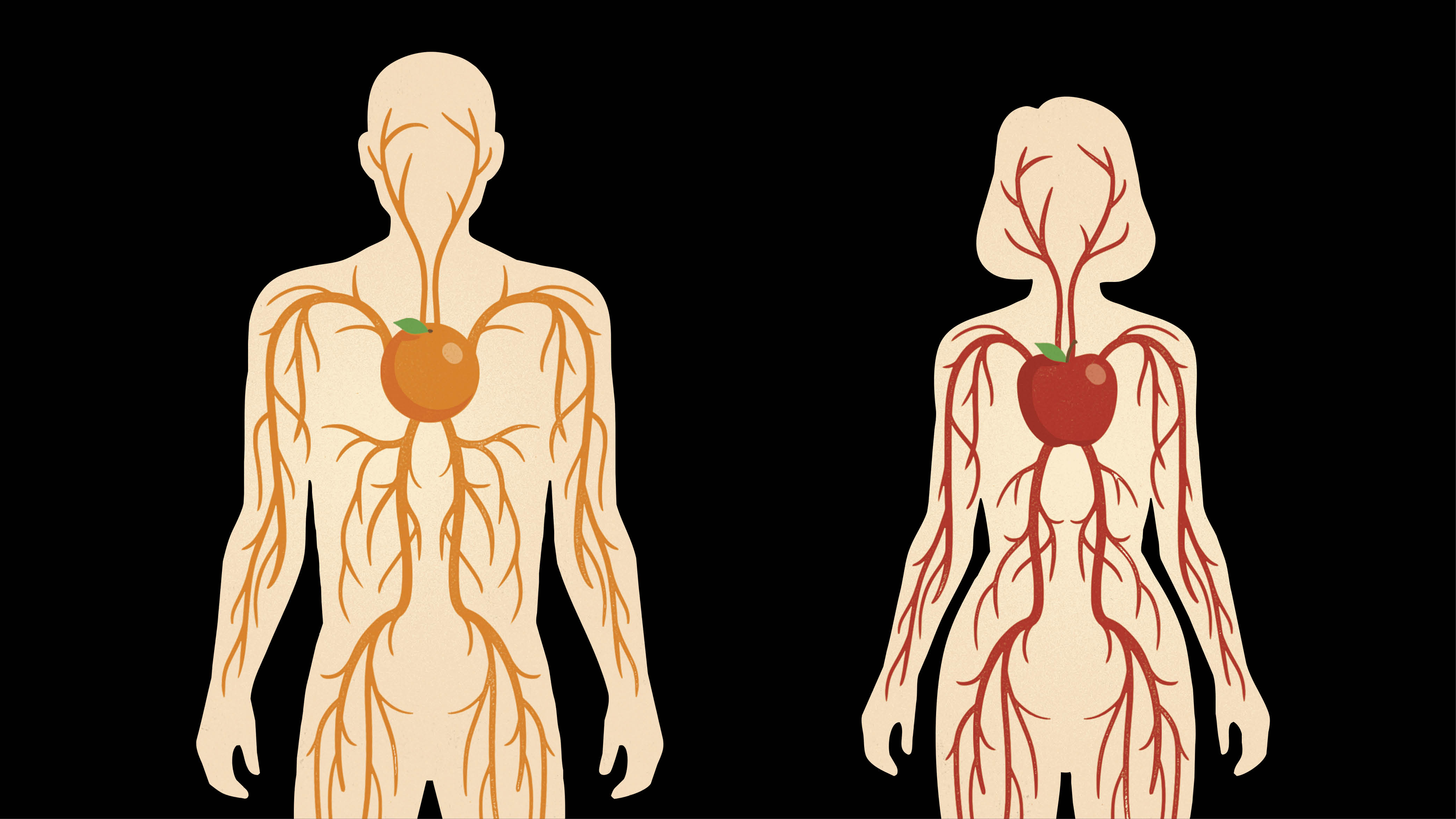

A man’s disease: Until just a few decades ago, that was how the majority of the medical world viewed heart disease. Cardiovascular research overwhelmingly focused on men, and treatment guidelines—from blood pressure medication to diagnostic criteria—were simply extrapolated to women.

This lack of research into the effects of gender and sex on heart health hid a grim reality: Heart disease is the leading cause of death for women, as it is for men. Women experiencing heart disease and heart attacks were going undiagnosed, receiving inappropriate treatment, or having their symptoms dismissed as anxiety.

Thanks to advocacy and federal policy changes requiring research to include women in their analyses, the medical world and the public have become more aware of the prevalence and presentation of heart disease in women. We now know, for instance, that the symptoms of a heart attack can look very different in women than the crushing chest pain that men often experience. Women are more likely to experience pain in other parts of the body, lightheadedness and flu-like symptoms. Campaigns by the American Heart Association and others teaching patients and providers to recognize these symptoms have helped double awareness of heart disease in women and may have played a role in declining death rates.

Despite these forward strides in research and communications, worrying trends persist: Young women are being hospitalized for heart attacks at increasing rates, according to a 2018 study published in the journal Circulation. Meanwhile, women die from heart attacks at twice the rate of men, according to a 2023 study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. On top of that, women are still underdiagnosed, undertreated and under-researched, says Glen Pyle, PhD, professor of molecular cardiology and a member of the IMPART Network at Dalhousie Medicine. “Pretty much across the board, women have worse outcomes,” Pyle says. “That’s really a result of a failure of the system from beginning to end.”

Physiologists are working to close that gap. The questions they’re exploring range from sex differences in cardiovascular physiology to the role of menopause and hormonal changes in heart health. For physiologists, it’s crucial to stay up to date in what we know—and what we’re still learning—about the leading killer of women.

The Protective Role of Hormones

For years, one of the reasons researchers gave for excluding women from studies was the unfounded belief that fluctuating hormones would confound results and make the population hard to study. As it turns out, those hormones are one of the most important reasons scientists studying the cardiovascular system should have been studying women all along—they play a key role in explaining the unique patterns and risk factors of heart disease in women.

There’s a kernel of truth to the idea that heart disease is more prevalent in men. At younger ages, men do have a four- to five-fold higher risk of developing heart disease compared to women, according to an international 2017 study published in BMJ Global Health. Around midlife, however, that changes.

“We see this dramatic increase in women,” says Megan Wenner, PhD, an associate professor in the Department of Kinesiology and Applied Physiology at the University of Delaware. In a recent study presented at the 2024 American College of Cardiology’s Annual Scientific Session, researchers measured plaque buildup in the heart arteries of 579 postmenopausal women taking statins. Over the course of a year, average scores measuring plaque buildup increased twice as quickly in these women than they do in men.

Researchers have long attributed this pattern to menopause and the dramatic drop-off in estrogen that occurs during this transition, Wenner says. Sudden drops in estrogen are correlated with increased risk of heart disease in other groups of people, independent of age. For instance, young women who have their ovaries removed have a higher risk of heart disease than their peers.

Researchers are still working to understand the mechanisms for how estrogen boosts cardiovascular health—and why a drop-off in this hormone has such deleterious consequences for women. Wenner’s research focuses on the role of sex hormones, including estrogen, on the cells in blood vessels. This focus is particularly important because heart disease in women tends to manifest as dysfunction in the microvasculature as opposed to larger heart arteries, which is more common in men, Wenner says.

“Estrogen has receptors in almost every tissue within the body, so it does have direct effects on the vasculature,” she says. Estrogen plays an important role in blood vessel dilation; it stimulates the production of nitric oxide, which helps blood vessels relax. Some of Wenner’s research shows that estrogen can decrease activity in the sympathetic nervous system. It also regulates the constricting and dilating effects of a receptor involved in blood vessel function.

Of course, estrogen isn’t the only hormone that declines after menopause. Research from Wenner’s lab suggests that other sex hormones may play an important role in heart disease. In a 2024 study, Wenner’s lab looked at the health of blood vessels outside the heart in a group of healthy women between the ages of 18 and 70. They found that the biggest predictor of age-related declines in vascular function wasn’t estrogen but two other sex hormones: progesterone and follicle-stimulating hormone.

“There has been a lot of focus and attention on estrogen, and that’s for obvious reasons,” Wenner says. “We think that there could be some important roles for other hormones that have just been understudied.”

Remodeling the Heart

If estrogen has such a strong protective effect for the heart, why don’t we see clear benefits from hormone replacement therapy (HRT)? That question has intrigued Pyle for most of his career.

When Pyle first began his graduate training in physiology, it was assumed that HRT could only be beneficial to heart health. When it concluded in the early 2000s, the groundbreaking longitudinal Women’s Health Study began to unravel that assumption. Rather than protecting women from heart disease, HRT appeared to increase risk. “We’ve spent the last 15 years trying to look at why the study came to this conclusion,” he says.

More recent data have shown that HRT is unlikely to increase the risk of heart disease, but there’s still no strong evidence that it’s protective, Pyle says. His research supports a theory that after menopause, it’s not just that estrogen levels drop off but that the heart itself undergoes a radical transformation, a phenomenon researchers call “cardiac remodeling.” That transformation might include a change in the heart’s responsiveness to estrogen.

In a 2019 study published in the journal Acta Physilogica, Pyle’s team of researchers modeled menopause in mice by delivering a drug that caused their ovaries to stop producing estrogen. The researchers then compared the hearts of these “perimenopausal” mice to those of intact mice. They found that the hearts of the altered mice had changed on a cellular level even before menopause was complete: Protein complexes that regulate the contraction of the heart had become less active. And in response to drugs that stimulate estrogen receptors, the hearts of menopausal mice were less responsive to estrogen receptor activation—a finding that might explain why HRT is unable to recapture the benefits of estrogen.

“What we found is the heart didn’t lose its responsiveness to estrogen—its response changed,” Pyle says. “After menopause, the heart is fundamentally different than before the transition.”

Diabetes and the Heart

While for the first half of their lives, women do generally have a lower risk of heart disease than men, that’s not true for a substantial portion of the population. For the roughly 14% of U.S. women with diabetes, regardless of age or menopausal status, heart disease poses just as great a risk as it does in men, says Judith Regensteiner, PhD, director of the Ludeman Family Center for Women’s Health Research and distinguished professor of medicine at Colorado University School of Medicine. “Diabetes eliminates the protection that people think is afforded by the hormones in premenopausal women.”

And these women fare even worse compared to men with diabetes. “The consequences of type II diabetes on the [female] heart are more severe than in men—women have heart attacks more often, and those heart attacks more often kill them,” Regensteiner says.

Regensteiner and her lab are looking at how diabetes changes the cardiovascular system and the impact those changes have on the ability of men and women to function in both exercise and daily life. They found that the cardiovascular system appears to stiffen and lose functional capacity even before any other complications become obvious. “That is pretty startling,” Regensteiner says.

While these changes occur across genders, they appear particularly pronounced in women. In one study, Regensteiner’s lab compared the VO2max, or maximum oxygen consumption, of 29 young men and women with diabetes to 35 non-diabetic peers. VO2max was 16% lower in men with diabetes compared to their healthy peers, but among women, that difference rose to 24%. That’s significant because VO2max isn’t just a measure of athletic performance—it also indicates one’s ability to function in daily life.

“It can mean the difference between being able to live a normal independent life and not being able to live a normal independent one,” Regensteiner says.

The Future of Clinical Practice

Since the 1990s, cardiovascular research may have become sex- and gender- inclusive, but the decades-long focus on men has an important lasting consequence. Men and women are still, almost uniformly, diagnosed using the same tools and prescribed the same treatments. “It’s just not based on evidence,” Regensteiner says. While these therapies have been rigorously tested for safety and efficacy in men, the same can’t be said for women.

Already, there is evidence that some long-established medical practices are much less effective in women than in men. For example, research suggests that women have lower levels of troponin, a protein that the heart releases into the bloodstream when it’s damaged. For decades, troponin has been used as a diagnostic biomarker for heart attacks. Too often, however, women who experience heart attacks will release too little of this protein to meet diagnostic criteria.

“There aren’t specific guidelines for treatment that take in this newer information,” Pyle says. Meanwhile, mounting evidence suggests that women are more likely than men to have adverse reactions to ACE inhibitors, used since the early 1980s and one of the most prescribed antihypertensive drugs today.

But the future of women’s heart health doesn’t just involve testing already-established protocols to make sure they work for women, says Kristine DeLeon-Pennell, PhD, associate professor of cardiology at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Indeed, the future of women’s heart health is personalized. For example, DeLeon-Pennell has identified that after a heart attack, male and female immune systems behave differently as they work to clear damaged heart tissues. In the future, sex-specific therapies might consider this information to promote healthy immune responses and minimize chronic inflammation.

“Historically, clinical trials don’t stratify by sex,” DeLeon-Pennell says. “In the clinic, we need to start being more cognizant of the therapies that are working best in women versus those that work best in men.”

That’s where basic science and physiology research comes in, Pyle says. His lab is conducting pre-clinical research on hormone replacement therapies better designed to interact with the postmenopausal heart.

“Until you understand how the physiology differs, you can’t understand how the disease develops differently, and you certainly can’t design therapies that are sex-specific,” Pyle says. “Without that foundation of fundamental science, it’s a weak case for any sort of therapy.”

This article was originally published in the March 2025 issue of The Physiologist Magazine. Copyright © 2025 by the American Physiological Society. Send questions or comments to tphysmag@physiology.org.

The Physiologist Magazine

Read the Latest Issue

Don’t miss out on the latest topics in science and research.

Contact Us

For questions, comments or to share your story ideas, email us or call 301.634.7314.